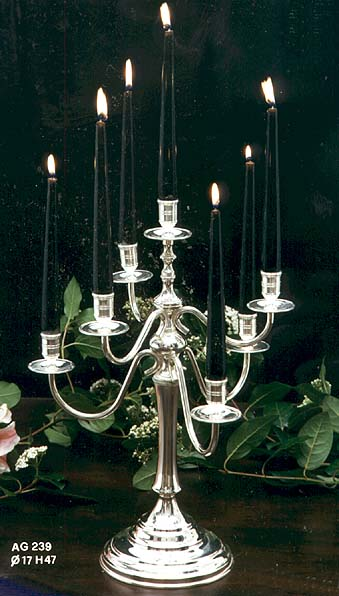

Silver candelabra

Silver candelabra: history and curiosities.

A little journey to discover the art of lighting.

Nowadays silver candlesticks are a luxury piece of furniture. Something we want solely for its beauty and without a practical purpose. But in the Renaissance they were not only art, they were also a necessity. Obviously candles and candelabras had been there for some time, but they were very different from what we are talking about. The candelabrum was already known to the Etruscans and the ancient Romans. Two types of candlesticks became widespread in Rome: a bronze one consisting of a shaped stem and four animal-paw feet for purely domestic use; the other, larger, in marble or richly decorated bronze, installed in places of worship and public buildings. Around the 8th century they were established in Christian places of worship and those produced with gold and silver were not rare. During the Romanesque period the object underwent some variations, such as that of column-shaped candelabra resting on decorated bases.

But it was in the fifteenth century that, under the pressure of the “humanistic revolution” of the Renaissance, silver made its triumphant entry into everyday life. Losing its status as the exclusive material of sacred and royal art (along with gold) and considered its greatest availability, silver became the hallmark of the bourgeoisie. In the homes of the rich, silver could be found everywhere: on the table, with plates, cups, salt shakers and, finally, knives and forks, of various shapes and sizes. For personal hygiene there were jugs and basins. In the rest of the house it was present in the form of ornaments, centerpieces and candlesticks in sumptuous-looking silver, enriched with precious stones, gilding and enamels. Here we note the true art of Florentine silverware, capable of combining the usefulness of common objects with great artistic expressiveness.

Silversmithing was considered an art equal to painting and architecture and many celebrated artists such as Ghiberti, Brunelleschi and Benvenuto Cellini began their apprenticeships as silversmiths. Mannerism, to the simplicity and linearity of classical forms, preferred the complexity and the invention of symbols and erudite themes, exasperated and grotesque forms, richly decorated and elaborate objects. The most famous example is the salt cellar created by Benvenuto Cellini for Francesco I, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Silver lent itself well to this type of work both for its ductility and for its high ability to reflect light. Candelabra in particular made the most of this ability, reflecting the light produced by the candle itself and increasing its brightness. This made silver candlesticks not only the most beautiful, but also the most efficient.